"You cannot imagine how much progress I see myself making every day. "What remedies are these that have done so much for you?" you say. "Send them to me too!" Indeed, I am longing to shower you with all of them. What gives me pleasure in learning something is that I can teach it. Nothing will ever please me, not even what is remarkably beneficial, if I have learned it for myself only. If wisdom were given to me with this proviso, that I should keep it shut up in myself and never express it to anyone else, I should refuse it: no good is enjoyable to possess without a companion. So I will send you the books themselves, and I will annotate them too, so that you need not expend much effort hunting through them for the profitable bits, but can get right away to the things that I endorse and am impressed with."

Seneca,"Letter 6", Seneca: Letters on Ethics To Lucilius, translated by Margaret Graver and A.A. Long

"Come now, show me what progress you're making in this regard. Suppose I were talking with an athlete and said, Show me your shoulders, and he were to reply, 'Look at my jumping-weights.' That's quite enough of you and your weights! What I want to see is what you've achieved by use of those jumping-weights. 'Take the treatise On Motivation and see how thoroughly I've read it.' that's not what I'm seeking to know, slave, but how you're exercising your motives to act and not to act, and how you're managing your desires and aversions, and how you're approaching all of this, and how you're applying yourself to it, and preparing for it, and whether in harmony with nature or out of harmony with it. If in harmony, give me evidence of that, and I'll tell you whether you're making progress; but if out of harmony, go away, and don't be satisfied merely to interpret those books, but also write some books of that kind yourself. And what good will that do you? Don't you know that the whole book costs only five denarii? So do you suppose that someone who interprets is worth more than five denarii? Never look for your work in one place, then, and your progress in another."

Epictetus, Discourses 2.1, translated by Robin Hard

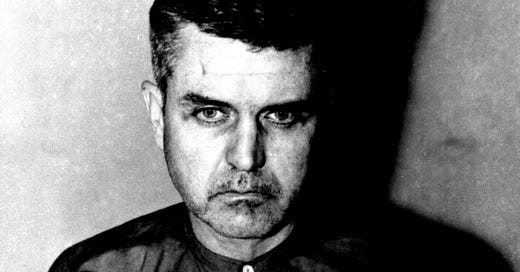

James Stockdale, for those who aren't familiar, was the senior-most US Navy officer taken as a Prisoner of War by North Vietnam. He spent seven and a half years in North Vietnam’s most notorious prison camp, where he was subjected to torture and absolutely inhumane conditions. Despite his injuries - physical, mental, and spiritual - he endured and forged the sagging US prison population into an effective resistance group. Throughout this experience he relied upon Stoic philosophy, especially the Discourses and Enchiridion of Epictetus. Stockdale credited Stoic philosophy with preserving his spirit and will to resist even during the darkest moments of captivity.

In his second-most popular Substack entry, philosopher Massimo Pigliucci held up Stockdale as an example of fake Stoic, someone who merely employed Stoic teachings instrumentally in pursuit of unjust ends. In this case, being a Naval aviator who served unjust American interests Vietnam. To Pigliucci, this puts Stockdale in the same league as slimey self-help coaches and pick up artists, the likes of Andrew Tate, who flap their gums about being stoic while disregarding all of the ethical commitments of Stoicism with a capital S. He illustrates his point with a panel borrowed from Existential Comics, which is cynical1 even by my jaded standards.

My objection to Pigliucci's take on Stockdale is that it's an isolated demand for rigor. Pigliucci takes the one of the highest standards of Stoic ethics - the cosmopolitan Sage - uncharitably applies it to Stockdale, and leverages that into a No True Stoic argument.

Yet, in a seperate essay published on 21 July behind a paywall, Pigliucci excuses Seneca from meeting those same strict standards that he applied to Stockdale, essentially because nobody's perfect and we ought to cut the man some slack. After all, the worst thing Seneca ever did was lend his loyalt and support to one of Rome’s most degenerate emperors.

So here's my response to Pigliucci in a nutshell: you can denounce Stockdale and Seneca as hypocrites and fakers or you can hold them up as examples of men who did their best to reconcile Stoic doctrines with the messy complexity of the real world. What you cannot do is condemn Stockdale and canonize Seneca using the same rubric, it's an impossible contortion. The rest of this essay is dedicated to explaining why.

II

Calling US involvement in Vietnam controversial may be the least controversial claim that I make in this essay. The history and historiography of the war are ideological battlegrounds and have been since before the US effectively withdrew military support from South Vietnam in 1973. I want to avoid arguing over historical minutiae and counterfactuals, what could/should have been done or anything like that. There are a few reasons for this; one, it's so complicated as to be beyond my pay grade (and frankly those of most non-specialists); two, whether the sum of two decades of US military activity in Vietnam complied with our current notions of jus ad bellum and jus in bello is mostly (although not entirely) irrelevant to the question of whether or not Stockdale merits inclusion in the Stoic canon. The more salient facts are those directly related to Stockdale himself, the events which he was involved with, and what he could have reasonably achieved during the course of those events.

My line of argument therefore does not hinge on whether US actions in southeast Asia from the Fifties to the Seventies were moral, which would be like arguing over whether or not the Julio-Claudian dynasty was a moral regime. Instead, my argument hinges on how Stockdale's own level of moral responsibility during the events of 1964 -1973 compares to Seneca's level of moral responsibility during Nero's reign. As we walk through the actions that defined the lives of these two men, what you'll see is that we cannot reasonably excuse one while condemning the other, and an attempt to do so would constitute an isolated demand for rigor.

In his short essay on LessWrong which defined this sort of sophic ploy, Scott Alexander tells us:

"At its best, philosophy is a revolutionary pursuit that dissolves our common-sense intuitions and exposes the possibility of much deeper structures behind them. One can respond by becoming a saint or madman, or by becoming a pragmatist who is willing to continue to participate in human society while also understanding its theoretical limitations. Both are respectable career paths.

The problem is when someone chooses to apply philosophical rigor selectively

…

But if [the philosopher] only applies his new theory when he wants other people’s cows, then we have a problem. Philosophical rigor, usually a virtue, has been debased to an isolated demand for rigor in cases where it benefits [the philosopher]."

So an isolated demand for rigor is when someone applies a philosophical principle inconsistently: they are strict when using it to attack other people (stealing their cows) but permissive when they want relatively normal day-to-day lives. This is a form of hypocrisy, you’re being easy on your own tribe while going hard on the other.

If you’re wondering why I care so much about this in the first place, it’s the hypocrisy. Borrowing here from Hannah Arendt:

“Words can be relied on only if one is sure that their function is to reveal and not to conceal. It is the semblance of rationality, much more than the the interests behind it, that provokes rage. To use reason when reason is used as a trap is not ‘rational’…”

In the profession of arms i.e. amongst those of us who are entrusted to organize and apply violence on behalf of the state, philosophy is critical but often overlooked, a point argued by Andy Owen:

“Afghanistan also highlighted the need to have a framework in which to think about ethics. The law should do this, I thought, but, without the underlying explanations, laws get ignored. This is especially so when laws seem to be irrelevant to the specific local context or if the law becomes deprioritised, as when the value of the end goal – potentially saving your friends’ lives – seems higher than the punishment for breaking the law.

…

Clearly, knowledge of G W F Hegel’s dialectics wouldn’t help much when receiving incoming fire in a platoon house in Sangin in Afghanistan. Yet, for me, facing morally difficult decisions in a warzone made me realise the subjective values that had influenced my thinking. Acts that I saw as inherently right or wrong in the comfort of everyday life didn’t seem so black and white in this new context.”

We want moral soldiers2 who can act effectively and justifiably in the midst of what’s known in military jargon as VUCA: volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity. VUCA is not the sort of thing that lends itself to black-and-white legalistic thinking, and Stoicism fills that need. Stockdale is the most prominent example of a modern military Stoic. Through his actions he showed us that it was possible for mere men to overcome base instincts and take charge of their souls. His is a statue that I don’t want to see torn down, not for my sake, but for the sake of our soldiers who need a proximate example of the philosopher-soldier in modern war.

I want young soldiers to continue to be inspired by Stockdale not because he was a saint or sage, but because he never stopped striving towards sagehood. If our trigger-pullers and their chains of command pause to ask themselves “What Would Stockdale Do?”, then the Western civil-military complex will be better for it.

Pigliucci apparently used to believe that Stockdale was a Stoic, but at some point changed his mind. In “The varieties of bad stoicism”, he tries explains that his change of heart occurred because of what Stockdale knew during the Gulf of Tonkin incident (more on this later) while continuing to fight: "since Stockdale willingly fought an unjust war, and moreover knew that the war was started under false pretense and yet said nothing, he cannot possibly be considered a Stoic role model."

This is the demand for philosophical rigor. Yet, Pigliucci’s recent essay “In defense of Seneca” presents the ancient philosopher as a Stoic, despite his flaws and failure to live up to his own ethical standards. I took a great interest in this essay, so much so that I subscribed to Figs in Winter just to get past the paywall and read it. Pigliucci’s apologetics for Seneca aren't wrong, in fact I agree with most of what he wrote, but they isolate his demand for ethical rigor with Stockdale. Pick both or neither, you can't have only one.

Before I continue, I want to make something very clear: I have immense respect for Massimo Pigliucci’s work, and if you take this essay to be an attack on the man or his broader efforts at making the world a better place through public philsophy, then you’re wrong.

III

Seneca has a something of a mixed reputation as a philosopher. On one hand, his writings - which ranged from pre-scientific treatises on natural philosophy, to epistles, to tragedies - are some of the most eloquent and complete that have survived from Antiquity. Seneca crafted detailed, articulate, and stirring arguments which urged his audience not to concern themselves with externals such as wealth, power, and badges of office, but rather to dedicate their attention to pursuing virtue and mastering the only thing they could really control: their internal states.

This sounds nice and virtuous, but is complicated by the fact that Seneca evidently struggled throughout his life to practice what he preached. Born the second son of an equestrian family, he rose to become one of the wealthiest men in the Roman Empire as a senator and high ranking member of the imperial court.

After being exiled to Corsica by the emperor Claudius in 41 CE, Seneca could have resigned himself to living a simple and austere life at the fringes of the empire, but instead he worked his way back into the good graces of imperial power. In 49 CE, Seneca was recalled from exile at the behest of Agrippina, the last wife of the emperor Claudius and the mother of Nero. Seneca tutored the young Nero and would serve as one of his closest advisors after Agrippina's manoeuvrings put him on the throne following Claudius' death in 54 CE. To secure Nero's position, Agrippina had Claudius' other son Britannicus murdered, which was not very ethical of her, but was par for the course for the Julio-Claudian dynasty. Despite the degeneracy of his milieu, Seneca continued his career in the Senate and stayed on as one of Nero's closest advisors.

Seneca was accused of exploiting his position in court for his own benefit, mostly through shady finance, but the jury is out on how credible these accusations are. In their commentary on the Graver and Long translation of Seneca's letters on ethics, Elizabeth Amis, Shadi Bartsch, and Martha C. Nussbaum note:

"In Seneca's own lifetime one P. Suillius attacked him on the grounds that that, since Nero's rise to power, he had piled up some 300 million sesterces by charging high interest on loans in Italy and the provinces - though Suillius himself was no angel and was banished... for being an embezzler and informant."

Pigliucci bypasses Seneca's business practices much the same way that Seneca himself did, by citing the the Stoic categorization of wealth as an indifferent i.e. something that in and of itself neither benefits nor harms a person. He also notes that Seneca lost a great deal of his wealth when he was banished, although he clearly gained it back and then some when he returned to the seat of power.

Interestingly, Pigliucci also notes that Seneca "possibly (though not likely) triggered the bloody Boudica rebellion by suddenly calling in a vast amount of loans he had made to the Britannic aristocracy." I'm an amateur in the practice of philosophy, and not even that when it comes to history, but excusing exploitative financial practices because on a balance of probablilities they didn't trigger a war isn't exactly a strong testament to Seneca's sagely character.

Nero's reign from 54 - 59 CE, the quinquennium Neronis, is seen as relatively beneficent. The emperor received counsel of Seneca and the praetorian prefect Sextus Afranius Burrus. Between the two of them, Burrus and Seneca may have been able to temper the young emperor's worst tendencies, but they could only manage this for so long.

To return his mother's favour murdering his step-brother and potential rival, Nero had Agrippina herself murdered in 59 CE, which was an appalling crime even by contemporary Roman standards. Nevertheless, Seneca wrote the speech which Nero used to excuse his actions in the Senate. Defending the emperor's matricide probably wasn't a comfortable position for Seneca, and Pigliucci states that his actions were

"obviously not in line with Stoic principles, it is hard to know exactly what was going on in Seneca’s mind. He may, for instance, have calculated that by way of this move he was going to be able to rein in Nero some more, thus saving Rome from another bloody civil war. If that was his plan, it failed."

Things went badly for Seneca after that. Burrus died in 62 C.E., removing Nero's other moderating influence. That year, Seneca tried to retire but Nero kept him in service This happened again in 64 C.E. Seneca attempted to withdraw from court life, which was, per Pigliucci, "an attempt that succeeded only partially (he got to spend more time in one of his country estates), and only temporarily."

Only a year later, Seneca was implicated in the Pisonian conspiracy and ordered to kill himself. Pigliucci's take on this is that Seneca probably wasn't a conspirator, though his nephew Lucan was and it’s likely that Seneca had knowledge of the conspiracy. I interpret Pigliucci’s argument along the lines that holding knowledge of a conspiracy without informing the imperial authorities gives Seneca ethical credit comparable to being a conspirator himself.

I disagree with this stance, since because it equivocates bystanding with taking action. It may be true that "they also serve who stand and wait", but fence-sitting simply isn’t comparable to the risk incurred by actually taking decisive action against tyrannical powers.

In any case, in 65 C.E. Nero ordered Seneca to kill himself for his alleged involvement in the conspiracy. After settling his affairs, Seneca went ahead with an assisted death surrounded by friends, having had the chance to dictate his final words to a scribe. He made a pretty big deal out of the process, which was supposed to evoke the death of Socrates. Ironically, his submission to death (theatrical though it was) is the strongest evidence we have that Seneca lived in accordance with his Stoic convictions.

To sum up this section on Seneca, I"ll refer back to Amis et al.:

"In Seneca's defense, he seems to have engaged in ascetic habits throughout his life and despite his wealth. In fact, his essay On the Happy Life (De vita beata) takes the position that a philosopher may be rich as long as his wealth is properly gained and spent and his attitude to it is appropriately detached. Where Seneca finally ranks in our estimation may rest on our ability to tolerate the various contradictions posed by the life of this philosopher in politics."

IV

"And now, when the moment calls, will you go off and give a reading to show off your compositions, and boast about them, saying, 'Look how well I can put dialogues together'? No, that's not what you should be boasting about, man, but this: 'See how I never fail to attain what I desire, see how I never fall into what I want to avoid. Bring death before me and you'll know. Bring hardships, bring imprisonment, bring, ignominy, bring condemnation.' Such should be the display of that a young man offers when he leaves school… Let others study how to plead in the courts, or how to deal with problems, or with syllogisms, while you study how to face death, imprisonment, torture, and exile."

Epictetus, Discourses, Book 2.1, translated by Robin Hard.

James Stockdale graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy in 1946. He was accepted for flight training in 1949, worked as a test pilot from 1954 - 1959, and then convinced the Navy to send him to Stanford to for a Masters degree in International Relations. It was during his time at Stanford that he developed his interest in classical philosophy. His path into Stoicism began, in his own words, by a chance encounter with professor of philosphy Phil Rhinelander:

“Within 15 minutes, we had agreed that I would enter his two-term course in the middle. To make up for my lack of background, I would meet him for an hour a week for a private tutorial in the study of his campus home.

Phil Rhinelander opened my eyes. In that study, it all happened for me - my inspiration, my dedication to the philosophic life. From then on, I was out

of international relations and into philosophy. We went from Job to Socrates to Aristotle to Descartes. And then on to Kant, Hume, Dostoevsky, Camus. On my last session, he reached high on his wall of books and brought down a copy of the Enchiridion. He said, ‘I think you'll be interested in this.’”

Stockdale didn’t approach philosophy as a collection trivia, he studied it as mental martial art. He took the application of philosophy seriously. Knowing wasn’t enough, what mattered was doing:

“Everything I know about Epictetus I've developed myself over the years. It's been a one-on-one relationship. He's been in combat with me, leg irons with me, spent month-long stretches in blindfolds with me, has been in the ropes with me, has taught me that my true business is maintaining control over my moral purpose, in fact that my moral purpose is who I am. He taught me that I am totally responsible for everything I do and say; and that it is I who decides on and controls my own destruction and own deliverance. Not even God will intercede if He sees me throwing my life away. He wants me to be autonomous. He put me in charge of me. ‘It matters not how straight the gate, how charged with punishment the scroll. I am the master of my fate, I am the captain of my soul.’”

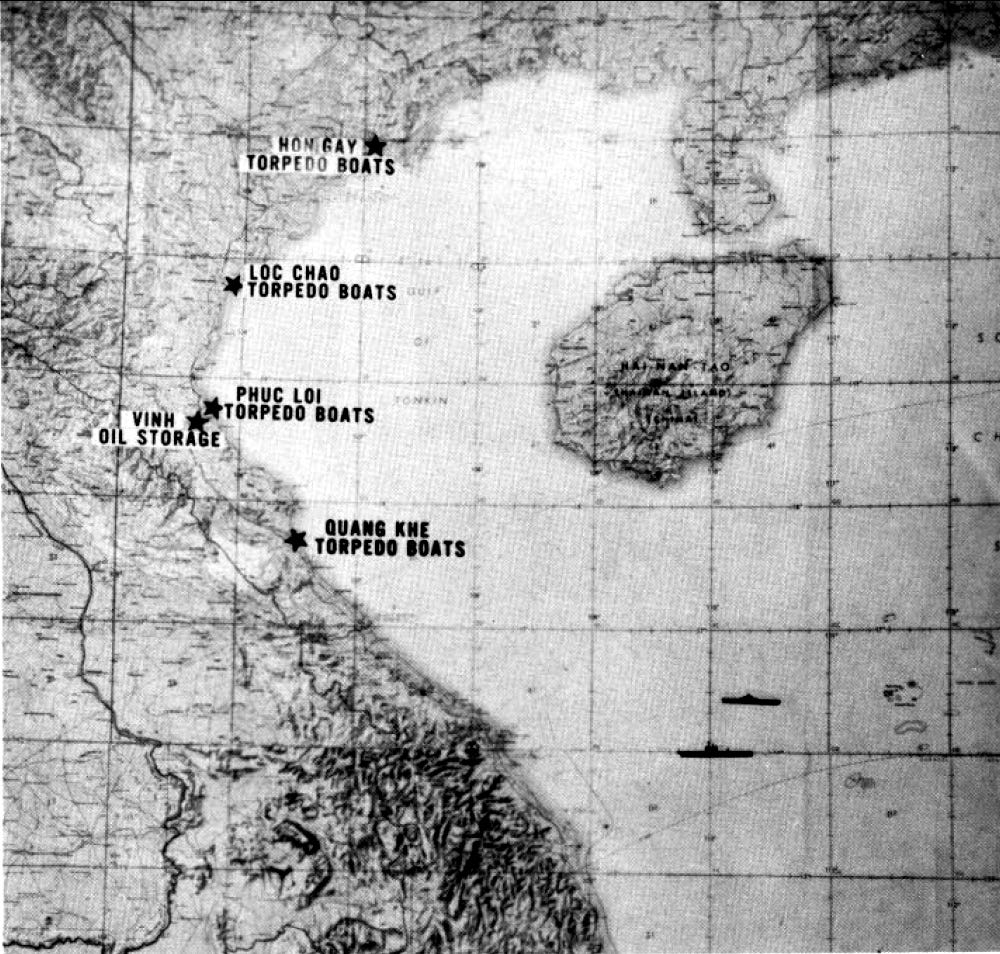

Moving forward a couple years to August 1964, Stockdale was in command of fighter squadron onboard USS Ticonderoga. On August 2nd, Stockdale's squadron was dispatched to support American ships who were in contact with North Vietnamese torpedo boats. The squadron engaged the torpedo boats as they attempted to break contact. On August 4th, Stockdale's squadron was again dispatched in response to an alleged second attack by the North Vietnamese. Unlike the engagement two nights prior, there weren't any North Vietnamese forces for the squadron to engage. Nevertheless, the American ships involved blasted away at phantoms in the fog. President Johnson used these events to justify a dramatic escalation in US military commitment to the Vietnamese theatre of war. The engagements and American response are known collectively as the Gulf of Tonkin incident.

Stockdale's squadron was ordered to execute the first American air strikes into North Vietnamese territory, known as Operation Pierce Arrow. The targets selected for Pierce Arrow were petroleum storage and torpedo boat facilities.

Stockdale recalled being surprised at the order to engage in "retaliatory" strikes since the alleged second attack was a fiction borne from confusion and willful misunderstanding. Following his repatriation from North Vietnam, he was very clear in his conviction that the US military efforts in Vietnam lacked a guiding moral centre. Here is an excerpt from a lecture he delivered to the Marine Amphibious Warfare School in in 1995:

"[Clausewitz] said: "War is an act of violence to compel the enemy to do your will." Your will, not his will. We are in the business of breaking people's wills. That's all there is to war; once you have done that, the war is over.

And what is the most important weapon in breaking people's wills? This

may surprise you, but I am convinced that holding the moral high ground is

more important than firepower. For Clausewitz, war was not an activity

governed by scientific laws, but a clash of wills, of moral forces..I had the wisdom of Clausewitz' stand on moral integrity demonstrated to me throughout a losing war as I sat on the sidelines in a Hanoi prison. To take a nation to war on the basis of any provocation that bears the smell of fraud is to risk losing national leadership's commitment when the going gets tough. When our soldiers' bodies start coming home in high numbers, and reverses in the field are discouraging, a guilty conscience in a top leader can become the Achilles heel of a whole country. Men of shame who know our road to war was not cricket are seldom those we can count on to hold fast, stay the course.

As some of you know, I led all three air actions in the Tonkin Gulf affair in the first week of August 1964. Moral corners were cut in Washington in our top leaders' interpretation of the events of August 4th at sea in order to get the Tonkin Gulf Resolution through Congress in a hurry. I was not only the sole eyewitness to all events, and leader of the American forces to boot; I was cognizant of classified message traffic pertaining thereto. I knew for sure that our moral forces were squandered for short-range goals; others in the know at least suspected as much."

Here is another excerpt from the same lecture:

"The time interval between my finishing graduate school and becoming a prisoner was almost exactly three years, September 1962 to September 1965. That was a very eventful period in my life. I started a war (led the first-ever American bombing raid on North Vietnam), led good men in about 150 aerial combat missions in flak, and throughout three 7-month cruises to Vietnam I had not only the Enchiridion, but the Discourses on my bedside table on each of the three aircraft carriers I flew from. And I read them.”

You might read this as self-incriminating, Stockdale himself admits that he started the Vietnam War. But rush not to judgement, for there are things which must be taken into account.

The first is that Stockdale was giving himself too much credit, or rather, he was taking more than his fair share of the blame. He wasn't the commander of all American forces involved, not even close. He commanded a fighter squadron in 1964, which is nothing to sniff at, but it's a fraction of all of the air power on a single carrier. On his 1965 tour, he was the Commander of the Air Group (CAG) onboard USS Oriskany. From Wikipedia:

"After WWII through 1983, CAGs were typically post-squadron command aviators in the rank of commander. Though the CAG was in command of the air wing, he functioned as a department head reporting to the carrier's commanding officer once the wing embarked."

That is to say, Stockdale wasn't the most senior commander on the carrier, nor in the fleet, let alone "leader of American forces to boot." The doctrine of command responsibility does not absolve followers of guilt for their actions committed while following unjust orders, but it does place the responsibility for issuing those orders on the commander. The responsibility for the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution rests firmly with American strategic leadership, especially Johnson and McNamara. Stockdale’s role in the incident was instrumental not original.

I should also add that while the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution is commonly cited as the start of the Vietnam War, this is based on narrow USA-centric view of what was in fact a much larger regional conflict. In fact, the USA had been involved in the post-colonial civil war between North and South Vietnam for a number of years prior to the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, conducting what we now call "hybrid operations", which are characterized by strategies which fuze military and non-military means in pursuit of strategic goals, while keeping these activites below the threshold of conventional war. Not all war is characterized by warfare in the conventional sense, and the USA was already at war in the Vietnam by 1964. The Gulf of Tonkin Resolution and Operation Piercing Arrow were a tipping point from hybrid warfare into overt combat operations. You may believe that bombing for peace is like fucking for virginity, but in reality it’s not so simple. Stockdale's guilty conscience may be taken as evidence of contrition for the role he played in an unjust and ill-considered escalation of force, but he doesn't get sole-authorship of history and shouldn’t shoulder the blame for strategic decisions which were made over his head.

V

"You should take no action unwillingly, selfishly, uncritically, or with conflicting motives. Do not dress up your thoughts in smart finery: do not be a gabbler or a meddler. Further, let the god that is within you be the champion of the being you are - a male, mature in years, a statesman, a Roman, a ruler: one who has taken his post like a soldier waiting for the Retreat from life to sound, ready to depart, past the need for any loyal oath or human witness. And see that you keep a cheerful demeanour, and retain your independance of outside help and the peace which others can give. Your duty is to stand straight - not be held straight."

Marcus Aurelius, Meditations 3.5, translated by Martin Hammond

There are some interesting parallels between Seneca and Stockdale. They both observed and participated in environments which are characterized by injustice in the historical narrative: the court of Claudius and the Gulf of Tonkin. Both depart from these environments, exile in the first case and sailing home in the second, yet both return to the conflict zone of their own volition. Seneca yearned to return to Rome and his wish was granted. Stockdale was promoted, given command of a carrier air wing, and sailed for Vietnam in 1965. Both fulfilled the duties of their stations to the best of their abilities, and in doing so were undone. This is where their lines diverge.

Seneca wrote a lot about enduring while Stockdale endured. Seneca chose to end his own life with the best means and support available to him, and died in a bath surrounded by friends and family. Stockdale may have wished to have been so blessed.

Pigliucci provides a pretty glib summary of Stockdales time as a Prisoner of War in Hoa Lo prison:

"When his plane was hit he parachuted himself out of the cockpit and saw that he was about to be apprehended by the enemy. He told himself that he was going to “enter the world of Epictetus,” meaning that he would essentially be a slave for at least five years. Turns out, he had been optimistic: he spent the years between 1965 and 1973 in the so-called Hanoi Hilton, a high security Vietnamese prison for enemy combatants. He was tortured and occasionally put in isolation, but survived by keeping firm in mind the above mentioned fundamental rule of life, the distinction between what was up to him (very little) and what was not (a lot)."

To be clear, Stockdale was the senior aviator in his wing and that meant that he personally led ~150 strike missions himself. The comic panel that Pigliucci uses as a caricature of Stockdale presents a modern-looking fighter jet dropping dumb bombs with impunity on terrified villagers3 which is artistic license at the expense of truth. Stockdale led missions from the cockpit of an A-4 Skyhawk (a much less capable aircraft than the stealthy aircraft of today) while flying through dense air defence zones. The North Vietnamese military wasn’t a ragtag group of desert dirt farmers, they had modern air defence systems (courtesy of the USSR and China), modern jet fighters, and an educated population with decades of warfighting experience. Stockdale’s missions took casualties; two of them on the first day of Piercing Arrow alone.

Stockdale ejected while flying at 500 knots, at such a low altitude that his parachute barely had time to fully deploy. He landed in the middle of a village, severely injured, and promptly received a gang beating at the hands of the villagers. But his trials were just beginning. The NVA recovered him and brought him to the Hoa Lo Prison (the "Hanoi Hilton"), where other aviators who survived bailing out were being held. This is how he described the indoc process into prison:

"The key word for all of us at first was fragility. Each of us, before we were ever in shouting distance of another American, was made to "take the ropes." That was a real shock to our systems - and as with all shocks, its impact on our inner selves was a lot more impressive and lasting and important than to our limbs and torsos. These were the sessions where we were taken down to submission and made to blurt out distasteful confessions of guilt and American complicity into antique tape recorders, and then to be put in what I call “cold soak,” six or eight weeks of total isolation to "contemplate our crimes." What we actually contemplated was what even the most self-satisfied American saw as his betrayal of himself and everything he stood for. It was there that I learned what "Stoic harm" meant. A shoulder broken, a bone in my back broken, and a leg broken twice were peanuts by comparison. Epictetus said: "Look not for any greater harm than this: destroying the trustworthy, self-respecting, well-behaved man within you."

When put into a regular cell block, hardly an American came out of that without responding something like this when first whispered to by a fellow prisoner next door: "You don't want to talk to me; I am a traitor." And because we were equally fragile, it seemed to catch on that we all replied something like this: “Listen, pal, there are no virgins in here. You should have heard the kind of statement I made. Snap out of it. We're all in this together. What's your name ? Tell me about yourself.” To hear that last was, for most new prisoners just out of initial shake down and cold soak, a turning point in their lives."

When Stockdale found out he was being cleaned up to make a propaganda reel, he dry shaved his hair into a reverse mohawk in protest. When his handlers shaved the rest of his hair, his response was to beat his own face with a stool to the point where his eyes swelled shut so that his image couldn't be used propaganda.

As the most senior officer in captivity, it was Stockdale's duty to take command of this fellow American captives, to organize their resistance, and to ensure that as many of them made it home as possible with their bodies and minds intact. He didn't sit on the fence, he didn't observe the resistance movement in silence, he embraced his duty - amor fati - and suffered horribly for it. He led a group of eleven aviators known as the Alcatraz Gang, who were singled out for extra harsh treatment because they took on leadership roles amongst the prisoners.

"They isolated my leadership team - myself and my ten top cohorts - and sent us into exile... All of us stayed in solitary throughout, starting with two years in leg irons in a little high-security prison right beside North Vietnam's "Pentagon" - their Ministry of Defense, a typical, old French building.

There are chapters upon chapters after that, but what they came down to in my case was a strung-out vengeance fight between the Prison Authority and those of us who refused to quit trying to be our brothers' keepers. The stakes grew to nervous-breakdown proportions. One of the 11 of us died in that little prison we called Alcatraz. There was not a man who wound up with less than three and a half years of solitary, and four of us had more than four years."

Seneca being confined to “only one” of his Italian countryside estates doesn't really sound like much of punishment by comparison. Frankly, it’s disingenuous of Pigliucci to characterize spending four years in solitary confinement, interrupted by torture, as "occasional isolation.”

Stockdale relates that amongst those who experienced more than two years of isolation, it was believed that the isolation was worse than the physical tortures. Men could acclimatize to pain, but their minds broke in solitude. But even as friends provided solace and solidarity, they were also a potential vulnerability to be exploited by the authorities. Stockdales recounted his own brush with Seneca's ultimate choice:

"At that time, the commissar of prisons had had me isolated and under almost constant surveillance for the year since I had staged a riot in Alcatraz to get us out of leg irons. I was barred from all prisoner cell-blocks. I had special handlers, and they caught me with an outbound note that gave leads I knew the interrogators could develop through torture. The result would be to implicate my friends in "black activities," as the North Vietnamese called them. I had been through those ropes more than a dozen times, and I knew I could contain material- so long as they didn't know I knew it. But this note would open doors that could lead to more people getting killed in there. We had lost a few in big purges - I think in torture overshoots - and I was getting tired of it.

It was the fall of 1969. I had been in this role for four years, and saw nothing left for me to do but check out. I was solo in the main torture room in an isolated part of the prison the night before what they told me would be my day to spill my guts. There was an eerie mood in the prison. Ho Chi Minh had just died and special dirge music was in the air. I was to sit up all night in traveling irons. My chair was near the only pane - glass window in the prison. I was able to waddle over and break the window stealthily. I went after my wrist arteries with the big shards. I had knocked the light out, but the patrol guard happened to find me passed out in a pool of blood but still breathing. The Vietnamese went to General Quarters, got their doctor, and saved me.

Why? It was not until after I was released years later that I learned that that very week, my wife, Sybil, was in Paris demanding humane treatment for prisoners. She was on world news, a public figure, and the last thing the North Vietnamese needed was me dead. There was a very solemn crowd of senior North Vietnamese officers in that room as I was revived. Prison torture, as we had known it in Hanoi, ended for everybody that night."

Seneca made a spectacle of his death to preserve his reputation and die with Roman honour. With the help of a slave, he cut his arteries, imbibed poison, and lay in a warm bath to make the blood flow faster.

Stockdale slit his own wrists quietly, alone in the darkness, without thought to his reputation, and not to spare himself indignity but to spare his fellow prisoners from torture. That is the death of a Stoic and the only reason we even know about it is because Stockdale's captors wouldn't grant him terminal success.

VI

Stockdale was a squadron then a wing commander, which meant he laboured under an enormous burden of responsibility for the outcomes of hundreds of person-years, literally hundres of thousands of person-hours. More importantly, he was directly responsible for the people themselves, their well being, and their lives, the sum of all their remaining person-years in the future. Whether the aviators he trained, flew, and was imprisoned with would live or die was a pressure that he would have carried all day, every day, without cease.

That is the burden of command. It's simply not the same as being an advisor, however highly placed. The privilege of being the voice behind the throne is that if the sword of Damocles falls it will miss your head. Seneca may have played a dangerous game at court, but at least he wasn't also playing it on behalf of subordinates whose lives depended on his split-second decisions.

This is where I diverge with some professional philosophers over the matter of conscientious objection. It's trivial to declare that soldiers have a moral duty to refuse to serve in unjust wars. I agree, this is true. Great! Glad we solved that.

But not so fast. Remember VUCA? Wars and warefare are volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous. Commentators can now review the historical record and declare that US intervention in Vietnam was unjust and everyone who didn’t resist military service are deserving targets of condemnation. But in the moment itself looking forward, things are never so clear.

You may recall Stockdale's remark when he was ordered to lead the first retaliatory air strikes against North Vietnam: "retaliation for what?" The thing is, he could be open about that after the war, but in the moment, I wonder if the he seriously considered the possibility of refusing his duty. It's evident that he was perfectly willing to fight the power at great personal cost from '65 - '73, so why not on that aircraft carrier in 1964?

It is the duty of every soldier to refuse to follow manifestly unlawful orders. The concentration camp truck driver's excuse of "only following orders" holds no weight when those orders are clearly and distinctly illegitimate based on their inherently immoral and criminal content. But it's easy for us, from the warmth and comfort of our armchairs in 2023, to judge what was or was not legitimate in the dark and fearful hours of August 5th, 1964. To spontaneously become a conscientious objector, in the midst of a military operation, is to call the whole thing a sham. Not just the op, not just the war, but the whole thing: the chain of command, the Commander-in-Chief, the submission of the military to civilian authority, all of it. Once you cross that Rubicon, you are playing by your own rules.

Everyone wishes that soldiers would quit in the face of unjust war. Every coffee shop anarchist's maxim is "what if they gave a war and nobody came?" The problem arises when it comes time to determine that this one is an unjust war when it's actually happening, when you’re in the middle of it, without the benefit of being able to read history backwards. After the USA withdrew military support in 1973, it took two years for the North to steamroll South Vietnam and the atrocities didn’t stop. They didn't stop after Linebacker II, it's just that the dying was being done by people that the student movement suddenly didn’t care about.

I'm not going to argue in support of the Lyndon Johnson's cassus belli, which was bullshit. Frankly, I think that if there was ever a discernible point when the USA decisively blew their claim to jus ad bellum, it was probably when they backed the Generals' coup against Diem in 1963. Regardless, it’s not clear to me that Stockdale was any more responsible for the actions of the Johnson administration than Seneca was for Nero’s.

Having a military that responds to the orders of elected civilian leaders is a cornerstone of democracy. When service members start arbitrarily deciding what is or is not a legitimate use of force, history tells us that the result isn't utopia. The bar for a service member to reject command authority is very high, and the bar rises commensurate with the rank in question. To clear that bar, the criminality of the order must be clear. Being ordered to execute civilians is manifestly unlawful, but being ordered to strike military targets as part of a continuum of escalation? In the ethics that govern our profession, that’s not so obvious. The anarchist’s maxim doesn’t generalize easily because you don’t actually want the holders of modern military power to employ those means according to their personal political leanings. The soldier’s duty to the state and its civilian leadership is a safeguard of democracy, but it’s side effect is often moral injury.

The fact remains that James Stockdale was a living proof of Stoic teachings. He wasn’t a saint, he wasn’t a sage, but he was a man who took the teachings to heart and applied them during the most demanding trials. He embodied the true spirit of Epictetus: he didn’t talk about his weights, he bared his shoulders. For this reason he merits inclusion in the Stoic canon as proof that the living can follow in the footsteps of the ancients.

Seneca reckoned that the Stoic sage was as rare as a phoenix, rising maybe once every 500 years. To err is human, and when those in positions of power make bad calls, the magnitude of their mistakes appears so much greater than ours even when they share common cause. In this light, Pigliucci argues that we ought to "consider Thomas Nagel’s concept of “moral luck”: if we feel so smugly superior to Seneca (or anyone else who acted badly under extreme circumstances), that’s just because we got lucky enough not to be seriously morally tested ourselves."

Yes, that's good advice indeed.

cynical with a lowercase c, not to be confused with the Cynic school of philosophy made famous by Diogenes.

In this essay I use the word soldier as a metonym for uniformed members of the armed services, regardless of environment or branch.

Corey Mohler, who writes Existentialist Comics, is clearly not an aficionado of military materiel. That’s fine, I enjoy most of his comics regardless. But I wonder if he actually thinks that you can hear anything on the ground from inside the cockpit of a fighter jet. It’s just such a blunt caricature that I can’t help but feel like it was motivated by anti-war politics. Again, if that’s Mohler’s thing that’s fine, but he really flattened a complicated story (and deeply interesting strain of philosophy) with that panel.

I live in the wilderness and I'm a hunter and a writer... I knew nothing about what you wrote and know nothing of it all besides Hollywood movies.

But I read everything you wrote and now I'm feel I know a tiny bit.

Thank you!