ADDENDUM ON STOCKDALE

What are the stakes when you argue about dead guys on the Internet?

In February 2023, Massimo Pigliucci posted his most popular Substack essay, “The varieties of bad stoicism”. In this essay, he used United States Navy Vice admiral (VADM) James Stockdale as an example of someone who successfully employed Stoic practices without being a practising Stoic. His argument for excluding Stockdale from the Stoic circle centres on the fact that Stockdale continued to serve as a naval aviator in the Vietnam theatre of war from 1964-1965 despite knowing that the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution was bullshit.

In July, I wrote a response to Massimo which defended Stockdale’s Stoic credentials by categorizing Massimo’s takedown as an isolated demand for rigor compared to his own defence of Seneca. In November, Massimo published a paywalled essay “The problem with presentism” which elaborated on his criticism of Stockdale. After a period of reflection on my hasty reply, I wrote this addendum.

Part I of this addendum summarizes Massimo’s position on Stockdale’s (non-)Stoicism and highlights points where we diverge. Part II is a tangent (rant) on how we remember wars. Part III moves past the specific issue of whether Stockdale was a Stoic in order to raise some more important questions aimed at the core of what it means to be a moral agent in the profession of arms.1

Before we proceed, it bears mentioning that I don’t hold any personal ire towards Massimo. Indeed, I paid him subscription fees for the privilege of reading his essays. I’m bringing this discussion forward because I think it’s a useful vehicle for exploring a difficult and important question in military ethics: when is it acceptable for professionals-at-arms2 to refuse their military duties?

I

“The problem with presentism” is Massimo’s response to those who believe that Stockdale was a capital-S Stoic and exemplar of Stoic practise. Massimo is a professional philosopher and keeps a high-profile in the modern Stoic and rationalist movements. Even as modern Stoicism penetrates deeper into contemporary culture propelled by the popular work of thinkers like Massimo,Donald J. Robertson, and Ryan Holiday, self-identifying as a Stoic is still a niche alignment. It’s more common to integrate Stoic perspectives into other philosphical frameworks.

One of the deep reservoirs of modern Stoic acolytes is - unsurprisingly - the military. Stockdale is often held up in military circles as a case study in successful Stoic practise and a role model.3 For his part, Massimo agrees with the former and disagrees with latter. He argues that “Stockdale’s use of Stoicism is an example of a (successful!) life hacking, but not of actually practicing the philosophy.”

My analysis of Massimo’s argument can be rolled up in five lines:

Stockdale studied Stoic philosophy; and

Stockdale successfully applied Stoic practises in captivity; however

Stockdale had direct, first hand knowledge that the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution was based on an untrue account of what actually happened from 02 - 04 August 1964; and

Stockdale continued to fulfill his duties as a naval aviator, did not go public with what he knew, and did not resign in protest; therefore

Stockdale did not apply the Stoic principle of justice to the degree necessary to merit inclusion in the Stoic canon, or even be considered a Stoic at all.

Critics in notes and the comment sections raised the fact that aside from the sagely Epictetus, the classical Stoic trinity includes Marcus Aurelius (emperor), Seneca (senator, financier, and eminence grise to Nero), neither of whom can be said to without ethical fault in the sense that they participated in and benefitted from the systemic immoralities of the Roman Empire.

Massimo dismisses this as presentism i.e. applying our contemporary ethical standards retroactively. He equates defence of Stockdale with a tu quoque attack on the Roman Stoics. Since humanity has made significant advances in moral philosophy since antiquity, Stockdale should be held to the higher modern standard.

Regarding the comparison between the military duties of Stockdale and Marcus Aurelius, Massimo wrote:

“There are plenty of people in the ‘60s and ‘70s who thought the Vietnam War was unjust. Marcus Aurelius, by contrast, was highly esteemed by even the most exacting of his peers as well as by multiple successive generations.”

Elsewhere in the comments, he wrote:

If Seneca and Marcus Aurelius exercised exemplary wisdom and justice in their own decisions, by the nature of their offices these decisions were (at least occassionally) made in support of unjust ends, not the least of which was perpetuating an unjust system of governance. That some (but not all, recall Seneca’s apology of matricide) of these unjust ends were normal and acceptable within the morality of the time could just as easily carry forward to 1964 - 1965, when the spectre of expanding Soviet influence in the third world prompted proxy wars by, with, and through allies of the West like South Vietnam.

II

In this section I’m going to indulge in a tangent on imperialism, war, and popular culture. You can bear with me or skip ahead to Part III. You’ve been warned.

Since the New Left decisively won the 20th century culture wars, America’s culture industry gazes back on the Vietnam War(s) through their bobo lens. These days, I wonder how many westerners (with the possible exception of the French) can summon a vision of the Indochina Wars in which American domestic strife doesn’t take centre stage.

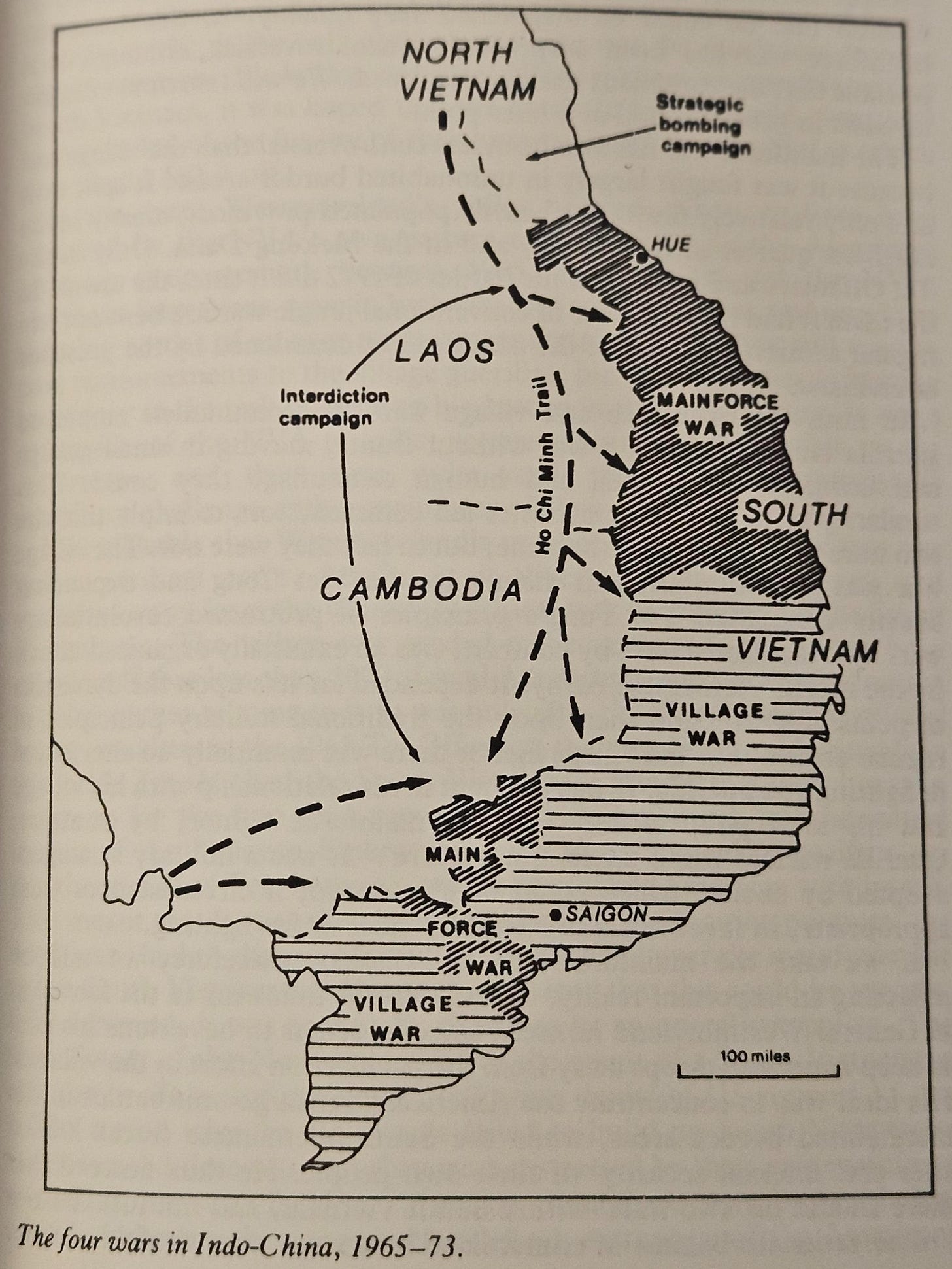

The prevailing narrative of the war(s) doesn’t give any agency (and therefore moral weight) to the other players, including North and South Vietnam. The fact that North Vietnam had been waging a long, deliberate, and subtle war against its neighbours since the end of the Second World War is never mentioned. That the US, South Korean, and Australian troop deployments were intended to shield South Vietnam from the NVA is also seldom mentioned, at least outside of professional literature. How many people even know that SK and AUS troops fought in Vietnam? The progressive hue and cry over US interdiction into Cambodia and Laos pushes out of frame the fact that the NVA was infiltrating whole divisions into the South through those countries.

In a real sense, I do not see a principled difference between Roman frontier wars and America’s “small wars” of the Monroe doctrine, containment doctrine, and domino theory. The character of war changes, but it’s fundamental nature does not. Great powers will push conflicts as far from their cultural, administrative, and economic hubs as possible, otherwise they don’t stay great or powerful. For Marcus Aurelius’ pre-modern empire, the Marcomannic Wars kept Germanic tribes away from Rome’s Adriatic ports and strategic lines of communication.

The Roman Empire seems less exploitative in western popular memory (compared to its contemporary competition) because our social order is directly downstream of it. The Romans may well have been primarily concerned with imposing an explicit system of laws and extracting taxes, which we’re supposed to be sympathetic to, but I doubt that comforted the locals who paid Roman taxes at the point of a gladius.

The modern rules-based international order is built on the back of western - mostly American - military hegemony. It’s been known since Corbett and Mahan that military power keeps the sea lanes open for international trade,4 secures the frontiers of stable economic zones, and secures the space for international courts and tribunals to do their work. Rules without enforcement are requests and the salient distinction between a code of law and a code of ethics is that the law is backed by force. This does not imply that might makes right, but right without might does not survive.

III

This post started out as a simple repost of my note to Massimo but it metastasized once I began pulling on loose discursive threads. As I became emotionally invested in defending the reputation of a dead man on the Internet, Epictetus lectured me from the bookshelf: “Go collect your Internet points, slave, don’t you know the whole Substack is only worth five denarii?”5 He’s right of course.

Yet the fact is that Massimo-contra-Stockdale drove a lot of engagement fascinated me. Something about it caught hold, and the very fact of this raises an important question. The question isn’t whether or not James Stockdale was a Stoic or merely stoic. No, the important question is why do we even care?

My impression is that Massimo’s takedown of Stockdale struck some military members on Substack as an attack on the collective ethos of western professionals-in-arms. Stockdale is held up as an exemplar of our deeply held ethical convictions and then one of America’s most prominent public philosophers hit us with “nah”.

The pro and contra Stockdale arguments have culminated, there just isn’t that much blood in the stone. In order to progress our understanding of the issues at stake, I see two open lines of inquiry:

Meta-ethics. Is it possible to be a “member in good-standing” of an ethical school when you hold offices which, instrumentally or indirectly, contribute to systemic violations of the ethical principles which you profess? Examples include Seneca, Marcus Aurelius, and of course, Stockdale. Personally, I’m not very interested in this line of inquiry since it is unlikely produce actionable deductions or “so-whats”.

Applied ethics. In the profession of arms, the duty of soldiers to refuse manifestly unlawful orders is well established under Law of Armed Conflict (LoAC) and International Humanitarian Law (IHL). Philosophers have extended this principle to argue that professionals-at-arms have a moral duty to deny their services in the prosecution of unjust wars.67 This raises two questions:

What are the epistemological and ethical criteria which must be met for professionals-at-arms to refuse orders which are lawful but immoral?

Epistemological criteria might include: how much do you need to know and how confidence must you have in that information before you refuse your orders?

The ethical criteria are constituted by the laws and customs of jus ad bellum.

In modern liberal demoracies, the profession of arms is subordinated to legitimate civilian authority - elected officials or appointments made by elected officials such as the US Secretary of Defense.8 This civil-military relationship alienates command of the armed forces from the profession of arms. Separation of power from the implements of violence is the first-and-foremost guarantor of liberal democracy and therefore upholding that seperation constitutes an ethical duty. Having established that professionals-at-arms have an ethical duty to remain subordinate to legitimate political authority:

Does refusal to comply with legitimate authority threaten the stability of liberal democracies? Obviously not if the conscientious objectors are low in number and dispersed. But the moral principles which motivate single objectors would presumably be normative for everyone, implying an ethical duty to mutiny.9 There are significant risks if we advocate that professionals-at-arms have a duty to mutiny based on their personal morals. Witness the rise, fall, and subsequent Balkanization of the Soviet Union.

What (if any) is the ethical difference between: professionals-at-arms refusing to engage in authorized violence for unjust ends and professionals-at-arms voluntarily engaging in unauthorized violence for just ends (“going rogue”)?

After I posted “In Defence of Stockdale”, I committed to critically examining the space between my morals and the ethics which govern my profession. These questions indicate that I’ve got a lot more work to do.

I see it as prima facie that there are legal-cultural regimes in which the organization and application of violence on behalf of legitimate authority is delegated to a professsional class of soldiers, sailors, aviators, Special Operations Forces, and their support personnel, which is collectively referred to as the “profession of arms” or the “military profession.” Not all occupations which feature violence are part of the profession of arms. Excluded for example are: police officers, security officers (armed or not), organized criminals, and insurgents. Whether the profession of arms is a true or useful concept is a subject of debate in defence circles.

I define professionals-at-arms as members of the profession of arms, inclusive of: ground, sea, air, space, cyber, intelligence, and special operations elements.

Stockdale wasn’t on the syllabus of any philosophy course that I took in school, even one that was dedicated to Stoicism. I was first introduced to Stockdale’s lectures through a Commanding Officer’s professional development session.

Just kidding, this Substack is currently worth approximately zero (0) denarii.

Massimo Pigliucci , excerpt from reply to Michael B. Cahill in the comments on “The problem with presentism”:

“Yes, most certainly justice overrides one's duty as a soldier. I would think that to be obvious. Soldiers kill, often for unjust reasons. War may be a sometimes necessary evil, but it is an evil nonetheless. And the one in Vietnam was definitely not necessary. And started on false pretenses. As Stockdale very well knew.”

Jessica Wolfendale, “Professional Integrity and Disobedience in the Military”.

Technically, members of the CAF swear or solemnly affirm their loyalty to the King, HRH Charles III (ol’ Liz in my day). I assume this is also the case in other Commonwealth countries. Regardless, the King doesn’t send Canadians to war, the Prime Minister and elected Members of Parliament do.

“mutiny” means collective insubordination or a combination of two or more persons in the resistance of lawful authority in any of Her Majesty's Forces or in any force cooperating therewith; (mutinerie)

I find myself currently reading Dereliction of Duty by H R McMaster, which I highly recommend.

The Khmer Rouge violently massacred a quarter of Cambodia's entire population in their killing fields. How is it "being a Stoic" to just let mass murder happen with impunity?